Continuing our reading list for this year

Dmitry Bykov – 100 books that everyone should read. Chapter Eight

This choice, like any choice, is subjective. I would never undertake to choose 100 major books in the history of mankind. Here are 100 books that I love the most myself. Besides, it seems to me that they are the best help to grow as a person – to the extent that reading can affect it at all. Dates are indicated according to the first publication or, if the book has been lying on the table for a long time, according to the last author's edition.

Leonid Leonov

THIEF (1927)

One of the main books about the Russian revolution – and what followed it: not everyone managed to fit into the NEP, into the peaceful petty-bourgeois life, which is becoming stuffy and menacing before our eyes. A revolution, no matter how bloody it may be, is a visitation of the country by God; everyone outgrows themselves, touches eternity, and only the worst will be able to return to ordinary human existence. And the best – such as Leonov's hero Dmitry Vekshin – rush to the bottom and become thieves: the criminal theme in Soviet prose of the twenties is one of the most significant. Vekshin cannot forgive himself for the atrocities, which he once easily found justification for, and hates former friends who have turned into officials or Soviet bosses. Plus, The Thief is a detective, where the investigator is the writer Firsov, Leonov's alter ego; this is a wonderful picture of the Moscow lower classes, secret gatherings, thieves' raspberries – a cruel and multi-layered narrative of post-revolutionary Russia, disappointed in the dream of world happiness. An exemplary social novel, large-scale and fascinating, imbued with Leon's eternal sense of anxiety and dissatisfaction; a separate author's luck – the fatal Manka Vyuga, a bandit from the former.

- The Thief had three editions – 1927, 1959 and 1982; in 1990, Leonov added something else. The edition of the thaw times, published most often, ends with a prophetic phrase: But nothing else was contained in the head breeze, except for that youthful and vain smell of any thaw.

WHEN TO READ: When it seems to you that your life has gone nowhere and all the great cataclysms only beckoned, and then deceived. Rest easy, it's always like that.

Andrey Platonov

EPIFAN GATEWAYS (1927)

The first real success of Andrey Platonov as a writer is a book where there is not yet the brilliant madness of Chevengur and Happy Moscow, but there is already everything that we call the Platonic worldview and style. The British engineer Perry builds locks on the orders of Peter – Peter generously favors the successful and mercilessly punishes those whose projects fail. During construction, Perry breaks through a layer of clay that holds water in the canals, and the canals are shallow, non-navigable.For this, he is subjected to an execution so terrible that the tongue does not dare to retell. Platonov guessed early on that the bottom of Russian life was broken, that the water was doomed to go into the sand – and instead of the promised rapid development, there would be continuous imitation and atrocity. The author was not even thirty, but Epiphany Gateways is a surprisingly mature work, in which the epic loftiness of the gaze is still combined with the painful Platonic pity for man. The Soviet Perries read it and understood everything, but they had nowhere to run.

- Andrei Platonov was married to Masha Kashintseva, whom he met in the flight writers department, where she served. He called her Eternal Mary and a muse. Oddly enough, he dedicated the Epiphany Gateways to her.

WHEN TO READ: It is well read in situations of loneliness and senseless waiting, for example, at the station or in line for help.

Yuri Tynyanov

DEATH OF VAZIR-MUHTAR (1929)

An autobiographical novel and perhaps even an autoepitaph disguised as a book about Griboyedov's last year. As a historical chronicle, of course, it is also invaluable – Tynyanov was a great philologist and an excellent connoisseur of the era. But the main value of the book is that it tells about the beginning of the reaction, about the historical turning points from great expectations to great fears. Speaking about how “people of the twenties disappeared with their jumping gait”, Tynyanov writes about the fate of his own generation – about the creators of a new science who believed in the triumph of an unprecedented system. What should a smart, strong, brilliantly gifted person do who does not need his country, although he would like to serve it with all his heart? What is a statesman to do without a state, a patriot without a homeland, a writer without literature? The image of Griboyedov is one of the most charming in Russian prose; telegraphic, as if breathless style, where pretentiousness is combined with almost rude mockery, and oriental ornateness – with forced laconicism, gaps in reticence, dark allusions – all this made Vazir-Mukhtar a favorite book of the Soviet intelligentsia. Abroad, she is also honored, but for various reasons they are poorly understood. However, even those who do not understand anything will read with enthusiasm – Tynyanov knew how to tell.

- Since 1929, Tynyanov suffered from multiple sclerosis, but continued to write, overcoming the disease.

WHEN TO READ: When overwhelmed by satiety, fatigue, hostility to the majority of friends and colleagues.

William Faulkner

NOISE AND FURY (1929)

One reader confessed to Faulkner that he had read The Sound and the Fury three times and understood nothing; Faulkner advised reading in the fourth. In fact, a detailed auto-commentary removes all questions: since childhood, Faulkner has been excited, like an obsession, by the memory of one day in the American South. In an old aristocratic family, impoverished and degenerated, a grandmother dies, and on the day of her death, the children are expelled from home. They play in the forest – a beautiful daughter, a brother secretly in love with her, and a weak-minded youngest child.It took Faulkner four monologues to tell the story of that day and the subsequent lives of the heroes: the day that the feeble-minded Benji, devoid of a sense of time, saw him; the dying confession of a suicide brother; the story of the beautiful Caddy – and, finally, the author's version of events, which leaves no secrets. It is not so difficult to restore the chronology of what is happening in this double stereoscopy, it is more difficult to endure Faulkner's view of things, in which human life really appears, according to Macbeth, as a story told by a fool: there is a lot of noise and rage in it, but there is no meaning. Incredibly dense prose, full of sounds, smells, shadows, highlights, suffering and fear; a truly ancient tragedy of rock, in which no one is to blame.

- Faulkner entered the Guinness Book of Records as the author of the longest sentence of 1288 words – from the novel Absalom! Absalom!

WHEN TO READ: When the feeling of the power of fate over your own destiny intensifies, the feeling of a blind force that has been twirling you since childhood.

Nikolay Zabolotsky

COLUMNS

POEMS (1929-1958)

In the second half of the twenties, Russian poetry fell silent – some went into translations, some into the newspaper, and some simply died. One group of Leningrad absurdists – the Oberiuts – managed to breathe in this airless space. Zabolotsky's Columns became a literary sensation: it was, undoubtedly, the lyrics – tragic, confessional, bilious – but she used the arsenal of notebook graphomaniacs: she mixed styles, parodied the classics, deliberately reduced pathos. Meanwhile, the era of the new philistinism was looking for its own language and its literary incarnation: Zoshchenko did it in prose, Zabolotsky did it in poetry. It is only necessary to remember that, in the language of a dull and narcissistic street, Zabolotsky remains a profound tragic poet, thinker, successor to Khlebnikov, who dreamed of a new worldwide brotherhood and a new language. Through the delirium and vulgarity of the Ivanovs and Obvodny Canal, weddings and cultural pubs, an amazingly clear and mournful voice breaks through – as the late Zabolotsky spoke in his understandable, traditional lyrical poems. None of his peers had such tearful anguish, such strange harmony, such depth and novelty – that's why the Columns and Zabolotsky's late lyrics look so mysterious against the background of other literature of that time, even quite worthy.

- Nikolai Zabolotsky was the largest translator of Georgian poets. By the way, he also translated Shota Rustaveli's poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin.

WHEN TO READ: When a terrible longing that finds no way out.

Boris Pasternak

SPEKTORSKY (1931)

Spektorsky is a novel in verse, an experience of a lyrical, but, moreover, a narrative poem with all the signs of a great narrative form. This is the story of a student, Seryozha Spektorsky, who, shortly before the revolution, at a New Year's party, fell in love with someone else's wife and became involved in a short, frivolous affair with her; and in the early twenties he met an old lover and was amazed at the change that had taken place.In front of him was the commissar, which at one time the horror of all Siberia, and today – uncompromising, cruel, perfectly rooted in new times. The path from the broken girl of the Silver Age in the commissars is described repeatedly – to take at least the “optimistic tragedy”, whose prototype was Larisa Reisner. For Pasternak, this is a metaphor for the entire Russian revolution, which was first a romantic lover of intellectuals, and after that with Mauser it appeared to take revenge on the illusions of that time. The revolution for Pasternak in general is the rebellion of scolded femininity, the revenge of all humiliated and offended (and humiliated in the former terrible world was primarily a woman); Maybe it was easier for him to love this storm. But regardless of the meaning, plot and pathos, these are Pasternak's most perfect verses, where he first owns all his abilities, not for a second without breaking into the famous metaphorical tongue -tied tongue. Everything is clear, strict, sad, accurately – and it is stated, sin to say, better than in the Dr. Zhivago.

- In 1930, when censorship was tightened, they did not want to release the novel with a separate book. Sacrifice by the fee, Pasternak refused to make changes-and achieved publication.

When to read: Well read in August, in the rain, after thirty.

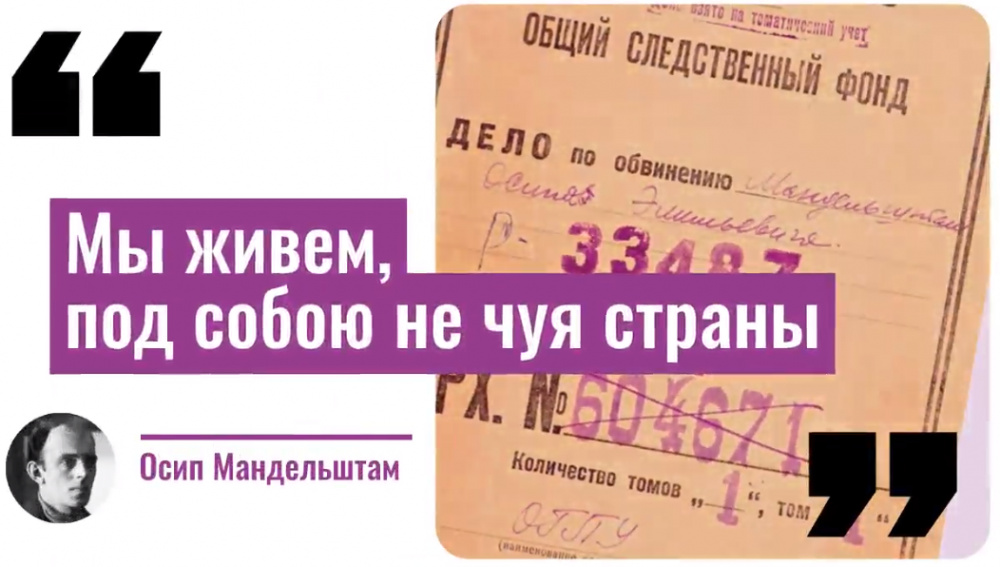

Osip Mandelstam

POEMS. Fourth prose (1917-1934)

Today, Mandelstam is the most popular Russian poet in the world, therefore, it is likely that its search is in the line of development of Western poetics: the search for the greatest concentration of thought, the rapid of its development. From the early lyrics: fundamentally clear, formally perfect, European-cultural-Mandelstam made the path to the illogicality and chaos of late verses, plunging deeper into himself, abandoning any supports and integuments. The modern reader – even a teenager – understands the verses of Mandelstam, who seemed dark and abstruse to his first readers: we are already used to thinking at such speed, and even the mysterious oratorio “Poems about an unknown soldier” with its dark and oppressive images of the Great and Last World War II today Almost does not require comment. Mandelstam – the voice of freedom, humanity, nobility among slogans, denunciations, marches, hoarse cries and warlike speeches; His lyrics are an embodied protest against the dominant, total simplicity, narrowness, self -interest. The late verses of Mandelstam are bubbles of oxygen in the airless space of Soviet culture from the times of terror; The sound wealth, whims of building, unpredictability of thought and impeccable possession of huge poetic tools turn it into a symbol of literary resistance and victory. Nabokov called him luminiferous – and he praised few.

- When the young poet complained to Mandelstam that he was not printed, – Mandelstam lowered him from the stairs, screaming after: “Did Homer print? And Jesus Christ printed? ”

When to read: When you feel that all sounds have stopped and world deafness has come; When it seems that there will no longer be any verses – and do not.

Ilya Ilf, Evgeny Petrov

Twelve chairs (1928)

Golden calf (1931)

The two most popular Soviet novels went into quotes immediately after publication. Brother Valentina Kataeva – a young Moscow journalist (formerly an Odessa threat employee) Eugene made friends in the editorial office of the Gudka with a feuilletonist Ilya Faynzilberg, an opera, skeptic, writer of poems in prose. Kataev invited them to write a novel about the search for treasures hidden in one of the twelve chairs of the Gambov headset. The co -authors took pseudonyms – Ilf and Petrov – and began to compose a satirical epic, the best of Russian Plutov’s novels. Bender, conceived as an adventurer and rogue, unexpectedly turned out to be a poet, an exposure of philistinism and, in general, the crown of all virtues. The Golden Calf, who had difficulty breaking into the seal, was already a deeply tragic novel about the all -conquering type of Koreiko – a beach, which, under the Soviet regime, is just as comfortable to steal, betray and adapt, as in any other system. “The irony was our response to the collapse of all values,” Petrov recalled in an unfinished book about Ilf. The cheerful, grotesque, fascinating dilogy – the main masterpiece of the South School – safely survived all the perturbations of the twentieth century and continues the triumphant procession through Riders and iPhones.

- Ilya Fainzilberg was six years older than Yevgeny Kataev, the co -authors never switched to you.

When to read: Absolutely always, especially healing during illness.

Pavel Antokolsky

Francois Viion (1934)

A dramatic poem-or a play in verses, an exceptionally stage, instantly memorable, musical, colloquial, romantic, platform, resurrecting the gloomy and high spirit of medieval Paris-the only reliable portrait of Francois Vione, ever successful of its later interpreters. This poem is the best composition of the temperamental and inexhaustible inventive master. Little where in Russian poetry the voice of a free and boundless space is so distinct – by the way, the space is not only geographical, but also cultural. More than theatrical and more minted poetry in the thirties, perhaps, was not there.

Yuri Krymov

Tanker Derbent (1937)

The Soviet production romance is more dynamic than another thriller – unless, of course, a real writer is taken to work, which was the engineer Yuri Krymov, who died in the war. In fact, we have before us the script of the film-catastrophe about a burning tanker, which manages to save against two terrible elements: fire and gouging, issued in the spirit of time for wrecking. Absolutely living heroes, a superbly organized narrative, hundreds of recognizable details – all this turns the “Tanker Derbent” into a unique monument to those Soviet times, when, it would seem, only fear should have been owned by everyone.But it turns out that not only. Krymov in general is one of the most attractive figures in Soviet prose: he would certainly be among the classics, if, except for this thing and later the story, “Feature” managed to write at least something else. However, for the status of a classic, one of his last letters would be enough for his wife, filled with blood in the last battle and a miracle of deciphered only twenty years later.

When to read: Laziness, idleness, loss of strength – then we need this injection of healthy activity.

Michael Bulgakov

Master and Margarita (1928-1940)

Probably, the most famous, cited and discussed Russian novel of the twentieth century is very ambiguous, like all masterpieces, and not completely clear to the author, who endlessly processed it. The story of the Satan invasion to Moscow mid -thirties, interwoven with a novel about the execution of Jesus and the betrayal of Pilate, is an amazingly accurate picture of the then Russia, in which without hellish forces probably could not do. The novel was written by and large for one reader – for Stalin, who was bred in the image of Pilate and partly in the image of Woland. The author’s message is quite distinct: destroy all this scum, it does not deserve another, with bureaucrats, appropriate and thieves otherwise – but keep the artist, protect the person of art. Then you will become force that, wanting evil, he does good. The ambiguity of this morality was obvious to Bulgakov himself, who, although he considered Stalin the most intelligent and strong man in the entire top (and maybe in the country), but of course, was not a Stalinist. Never ask for anything from those who are stronger than you, they will come and give everything themselves – there is nothing to argue with; But he pulls to add: However, then do not take it. For millions of readers, the novel turned out to be a terrible temptation, the justification of that very evil that turns good; In order to finally debunk this seductive idea, a postscript was needed in the form of the death of the author himself, who was forever disappointed in the hellish forces, no matter what they promise and no matter how spectacular they focused.

- As the widow of the writer Elena Sergeevna wrote, the last words of Bulgakov about the novel “Master and Margarita” before his death were: “To know … to know.”

When to read: The best time for this book is the class of the seventh, when its miracles do not yet look like a metaphor.